It’s very late. You’re alone. You were sleeping until suddenly you weren’t. You have to pee, or you turned over wrong and pulled something in your neck—but it doesn’t matter what woke you, because now you’re staring at the foot of your bed. The shadows are deep and heavy, as though something more than shadow crouches there, just beyond your mattress.

It’s very late. You’re alone. You were sleeping until suddenly you weren’t. You have to pee, or you turned over wrong and pulled something in your neck—but it doesn’t matter what woke you, because now you’re staring at the foot of your bed. The shadows are deep and heavy, as though something more than shadow crouches there, just beyond your mattress.

As you lie there, unable to move, you’re abruptly certain that something is about to drag itself up onto your bed. One of your feet is above the covers. You kicked it free of the blankets because you were too hot, and now your bare toes are inches from whatever is coming over the edge of your mattress, and you want desperately to move it to safety but if you do, if you even breathe, it’s going to know you know it’s there.

This tortuous, expectant dread is burned into my brain from early childhood, thanks to the Appalachian campfire story of Tailypo (also called Taily Po or Tailybones): a bobcat-like monster with pointed ears and a long, prehensile tail. When a starving hunter catches the beast and lops off its tail for a stew, he and his dogs are slowly but inexorably punished for the act.

First it’s only a moaning voice on the wind—“Tailypo, tailypo, I just want my tailypo!”—that keeps the hunter awake in his rural, isolated cabin. Then a scritching noise begins to stalk the walls, sharp nails digging into the seams, searching for a way in. That inhuman voice whispers, “Tailypo, tailypo, who’s got my tailypo?” before the dogs chase it off, though one by one, they fail to return.

Finally, inevitably, all the dogs are gone. The farmer lies alone in his drafty bed and the scritching has never been louder—until it stops. The clatter of nails on the floor betrays the monster’s approach, and then two clawed paws and mean red eyes inch up above the foot of his mattress. “You’ve got my tailypo,” the monster says, and… well, suffice to say, it goes on a retrieval mission, the level of gore in accordance to the age of the listeners.

For me, Tailypo (although I suppose we have a Frankenstein situation with the name) is fascinating not only because it’s a weird little monster that might disembowel me in my bed, but because it was only trying to live its weird monster life until a human disrupted it. In the legend, the hunter reaps what he sows, though neither he nor the monster are depicted as particularly evil.

There’s something poetic about that, and appropriate to the deep woods and mountains that spawned this story: you have to respect nature, and if you don’t, you’ll get what’s coming to you—but also, humans will act desperately when pushed to it, but it doesn’t make us evil, and at the same time, we aren’t automatically more deserving of life than anything else.

I return to these themes and ideas over and over again in my own writing: that everyone is capable of doing bad things (and almost anything can be justified if we try hard enough). That as much as we invade nature, nature has the power to invade us right back. And, of course, the deep horror of being in a place that should feel safe and familiar—but knowing, down to your bones, that something is watching just out of sight.

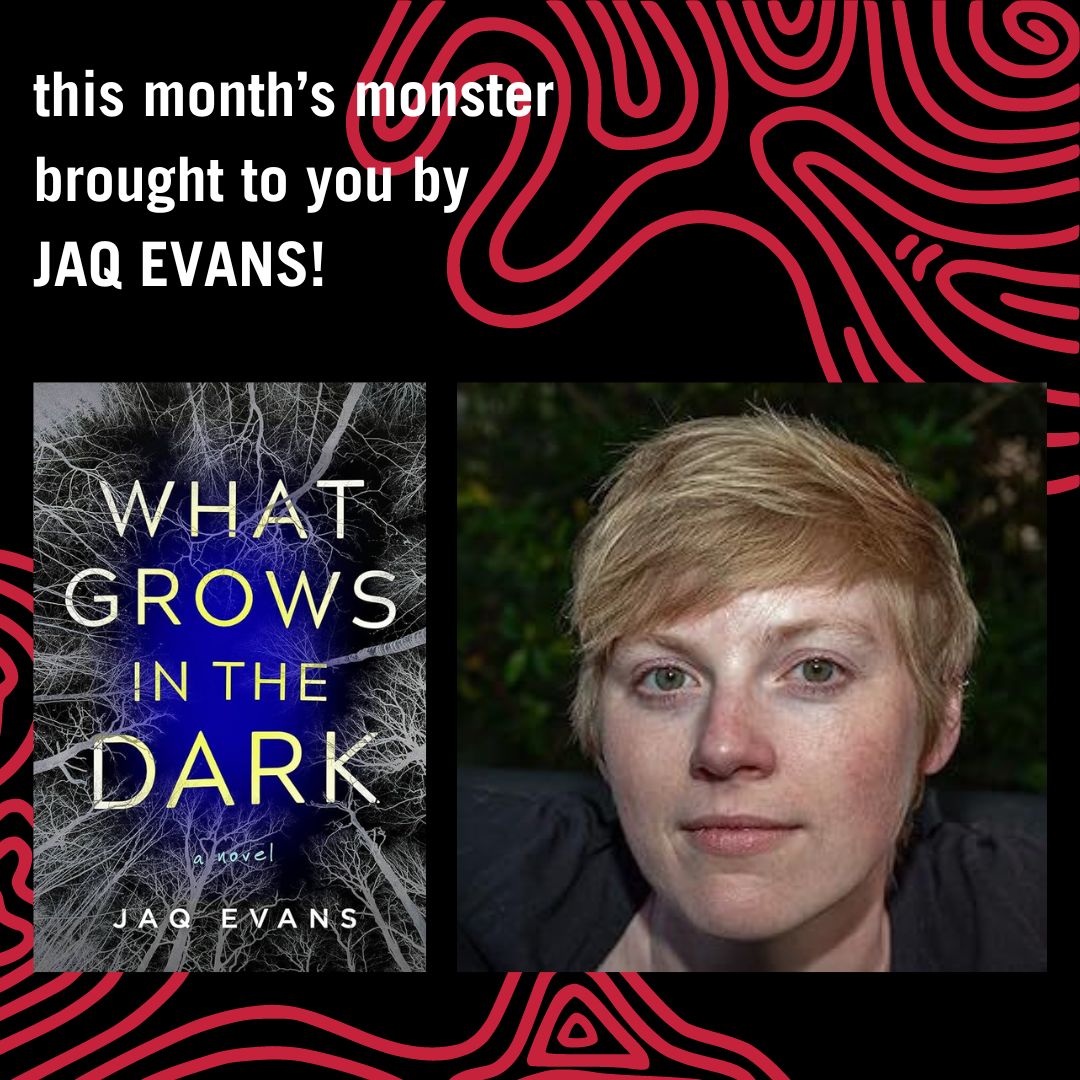

If you’re a fan of wild woods and what might be lurking in them, and worse, what might come into your home and force a reckoning you may not be ready for, my debut novel WHAT GROWS IN THE DARK could be up your alley! Available from MIRA / HarperCollins on March 5, 2024.

Jaq Evans grew up running around the woods in Virginia’s Blue Ridge foothills and now lives near different mountains in Seattle. A graduate of the Stonecoast MFA program, Jaq writes fiction, narrative nonfiction and poetry. What Grows in the Dark is her first novel.